Genocide

The government’s policy for East Bengal was spelled out to me in the Eastern Command headquarters at Dacca. It has three elements:-

(I) The Bengalis have proved themselves “unreliable” and must be ruled by West Pakistanis;

(2) The Bengalis will have to be re-educated along proper Islamic lines. The “Islamisation of the masses” — this is the official jargon — is intended to eliminate secessionist tendencies and provide a strong religious bond with West Pakistan;

(3) When the Hindus have been eliminated by death and flight, their property will be used as a golden carrot to win over the under-privileged Muslim middle-class. This will provide the base for erecting administrative and political structure in the future.

This policy is being pursued with the utmost blatancy.

For six days as I travelled with the officers of the 9th Division headquarters at Comilla I witnessed at close quarters the extent of the killing. I saw Hindus, hunted from village to village and door to door, shot off-hand after a cursory “short-arm inspection” showed they were uncircumcised.

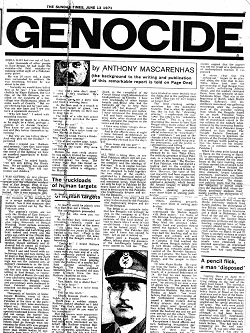

Anthony Mascarenhas

Published in The Sunday Times on 13 June 1971

ABDUL BARI had run out of luck.

Like thousands of other people in East Bengal, he had made the mistake — the fatal mistake — of running within sight of a Pakistani army patrol.

He was 24 years old, a slight man surrounded by soldiers. He was trembling, because he was about to be shot.

“Normally we would have killed him as he ran,” I was informed chattily by Major Rathore, the G-2 Ops. of the 9th Division, as we stood on the outskirts of a tiny village near Mudafarganj, about 20 miles south of Comilla. “But we are checking him out for your sake. You are new here and I see you have a squeamish stomach.”

“Why kill him?” I asked with mounting concern.

“Because he might be a Hindu or he might be a rebel, perhaps a student or an Awami Leaguer. They know we are sorting them out and they betray themselves by running.”

“But why are you killing them? And why pick on the Hindus?” I persisted.

“Must I remind you,” Rathore said severely, “how they have tried to destroy Pakistan? Now under the cover of the fighting we have an excellent opportunity of finishing them off.”

“Of course,” he added hastily, “we are only killing the Hindu men. We are soldiers, not cowards like the rebels. They kill our women and children.”

I WAS GETTING my first glimpse of the stain of blood which has spread over the otherwise verdant land of East Bengal. First it was the massacre of the non-Bengalis in a savage outburst of Bengali hatred. Now it was massacre, deliberately carried out by the West Pakistan army.

The pogrom’s victims are not only the Hindus of East Bengal — who constitute about 10% of the 75 million population — but also many thousands of Bengali Muslims. These include university and college students, teachers, Awami League and Left-Wing political cadres and every one the army can catch of the 176,000 Bengali military men and police who mutinied on March 26 in a spectacular, though untimely and ill-starred bid, to create an independent Republic of Bangla Desh.

What I saw and heard with unbelieving eyes and ears during my 10 days in East Bengal in late April made it terribly clear that the killings are not the isolated acts of military commanders in the field.

The West Pakistani soldiers are not the only ones who have been killing in East Bengal, of course. On the night of March 25 — and this I was allowed to report by the Pakistani censor — the Bengali troops and paramilitary units stationed in East Pakistan mutinied and attacked non-Bengalis with atrocious savagery.

Thousands of families of unfortunate Muslims, many of them refugees from Bihar who chose Pakistan at the time of the partition riots in 1947, were mercilessly wiped out. Women were raped, or had their breasts torn out with specially fashioned knives. Children did not escape the horror: the lucky ones were killed with their parents; but many thousands of others must go through what life remains for them with eyes gouged out and limbs roughly amputated. More than 20,000 bodies of non-Bengalis have been found in the main towns, such as Chittagong, Khulna and Jessore. The real toll, I was told everywhere in East Bengal, may have been as high as 100,000; for thousands of non-Bengalis have vanished without a trace.

The government of Pakistan has let the world know about that first horror. What it has suppressed is the second and worse horror which followed when its own army took over the killing. West Pakistani officials privately calculate that altogether both sides have killed 250,000 people — not counting those who have died of famine and disease.

Reacting to the almost successful breakaway of the province, which has more than half the country’s population, General Yahya Khan’s military government is pushing through its own “final solution” of the East Bengal problem.

“We are determined to cleanse East Pakistan once and for all of the threat of secession, even if it means killing of two million people and ruling the province as a colony for 30 years,” I was repeatedly told by senior military and civil officers in Dacca and Comilla.

The West Pakistan army in East Bengal is doing exactly that with a terrifying thoroughness.

WE HAD BEEN racing against the setting sun after a visit to Chandpur (the West Pakistan army prudently stays indoors at night in East Bengal) when one of the jawans (privates) crouched in the back of the Toyota Land Cruiser called out sharply: “There’s a man running, Sahib.”

Major Rathore brought the vehicle to an abrupt halt, simultaneously reaching for the Chinese made light machine-gun propped against the door. Less than 200 yards away a man could be seen loping through the knee-high paddy.

“For God’s sake don’t shoot,” I cried. “He’s unarmed. He’s only a villager.”

Rathore gave me a dirty look and fired a warning burst.

As the man sank to a crouch in the lush carpet of green, two jawans were already on their way to drag him in.

The thud of a rifle butt across the shoulders preceded the questioning.

“Who are you?”

“Mercy, Sahib! My name is Abdul Bari. I’m a tailor from the New Market in Dacca.”

“Don’t lie to me. You’re a Hindu. Why were you running?”

“It’s almost curfew time, Sahib, and I was going to my village.”

“Tell me the truth. Why were you running?”

Before the man could answer he was quickly frisked for weapons by a jawan while another quickly snatched away his lungi. The skinny body that was bared revealed the distinctive traces of circumcision, which is obligatory for Muslims.

The truckloads of human targets

At least it could be plainly seen that Bari was not a Hindu.

The interrogation proceeded.

“Tell me, why were you running?”

By this time Bari, wild eyed and trembling violently, could not answer. He buckled at the knees. “He looks like a fauji, sir,” volunteered one jawan as Bari was hauled to his feet, (Fauji is the Urdu word for soldier: the army uses it for the Bengali rebels it is hounding.)

“Could be,” I heard Rathore mutter grimly.

Abdul Bari was clouted several times with the butt end of a rifle, then ominously pushed against a wall. Mercifully his screams brought a young head peeping from the shadows of a nearby hut. Bari shouted something in Bengali. The head vanished. Moments later a bearded old man came haltingly from the hut. Rathore pounced on him.

“Do you know this man?”

“Yes, Sahib. He is Abdul Bari.”

“Is he a fauji?”

“No Sahib, he is a tailor from Dacca.”

“Tell me the truth.”

“Khuda Kassam (God’s oath), Sahib, he is a tailor.”

There was a sudden silence. Rathore looked abashed as I told him: “For God’s sake let him go. What more proof do you want of his innocence?”

But the jawans were apparently unconvinced and kept milling around Bari. It was only after I had once more interceded on his behalf that Rathore ordered Bari to be released. By that time he was a crumpled, speechless heap of terror. But his life had been saved.

Others have not been as fortunate.

For six days as I travelled with the officers of the 9th Division headquarters at Comilla I witnessed at close quarters the extent of the killing. I saw Hindus, hunted from village to village and door to door, shot off-hand after a cursory “short-arm inspection” showed they were uncircumcised.

I have heard the screams of men bludgeoned to death in the compound of the Circuit House (civil administrative headquarters) in Comilla. I have seen truck loads of other human targets and those who had the humanity to try to help them hauled off under the cover of darkness and curfew. I have witnessed the brutality of “kill and burn missions” as the army units, after clearing out the rebels, pursued the pogrom in the towns and the villages.

I have seen whole villages devastated by “punitive action.” And in the officers’ mess at night I have listened incredulously as otherwise brave and honourable men proudly chewed over the day’s kill.

“How many did you get?” The answers are seared in my memory.

ALL THIS is being done, as any West Pakistani officer will tell you, for the “preservation of the unity, the integrity and the ideology of Pakistan.” It is, of course, too late for that. The very military action that is designed to hold together the two wings of the country, separated by a thousand miles of India, has confirmed the ideological and emotional break. East Bengal can only be kept in Pakistan by the heavy hand of the army. And the army is dominated by the Punjabis, who traditionally despise and dislike the Bengalis.

The break is so complete today that few Bengalis will willingly be seen in the company of a West Pakistani. I had a distressing experience of this kind during my visit to Dacca when I went to visit an old friend. “I’m sorry,” he told me as he turned away, “things have changed. The Pakistan that you and I knew has ceased to exist. Let us put it behind us.”

Hours later a Punjabi army officer, talking about the massacre of the non¬ Bengalis before the army moved in, told me: “They have treated us more brutally than the Sikhs did in the partition riots in 1947. How can we ever forgive or forget this?”

The bone-crushing military operation has two distinctive features. One is what the authorities like to call the “cleansing process”; a euphemism for massacre. The other is the “rehabilitation effort.” This is a way of describing the moves to turn East Bengal into a docile colony of West Pakistan. These commonly used expressions and the repeated official references to “miscreants” and “infiltrators” are part of the charade which is being enacted for the benefit of the world. Strip away the propaganda, and the reality is colonisation — and killing.

The justification for the annihilation of the Hindus was paraphrased by Lt. Gen. Tikka Khan, the Military Governor of East Pakistan, in a radio broadcast I heard on April 18. He said: “The Muslims of East Pakistan, who had played a leading part in the creation of Pakistan, are determined to keep it alive. However, the voice of the vast majority had been suppressed through coercion, threats to life and property by a vocal, violent and aggressive minority, which forced the Awami League to adopt the destructive course.”

Others, speaking privately, were more blunt in seeking justification.

“The Hindus had completely undermined the Muslim masses with their money,” Col. Naim, of 9th Division headquarters, told me in the officers’ mess at Comilla. They bled the province white. Money, food and produce flowed across the borders to India. In some cases they made up more than half the teaching staff in the colleges and schools, and sent their own children to be educated in Calcutta. It had reached the point where Bengali culture was in fact Hindu culture, and East Pakistan was virtually under the control of the Marwari businessmen in Calcutta. We have to sort them out to restore the land to the people, and the people to their Faith.”

Or take Major Bashir. He came up from the ranks. He is SSO of the 9th Division at Comilla and he boasts of a personal body count of 28. He had his own reasons for what has happened. “This is a war between the pure and the impure,” he informed me over a cup of green tea. “The people here may have Muslim names and call themselves Muslims. But they are Hindus at heart. You won’t believe that the maulvi (mulla) of the Cantonment mosque here issued a fathwa (edict) during Friday prayers that the people would attain janat (paradise) if they killed West Pakistanis. We sorted the bastard out and we are now sorting out the others. Those who are left will be real Muslims. We will even teach them Urdu.”

Everywhere I found officers and men fashioning imaginative garments of justification from the fabric of their own prejudices. Scapegoats had to be found to legitimise, even for their own consciences, the dreadful “solution” to what in essence was a political problem: the Bengalis won the election and wanted to rule. The Punjabis, whose ambitions and interests have dominated government policies since the founding of Pakistan in 1947, would brook no erosion of their power. The army backed them up.

Officials privately justify what has been done as retaliation for the massacre of the non-Bengalis before the army moved in. But events suggest that the pogrom was not the result of a spontaneous or undisciplined reaction. It was planned.

It seems clear that the “sorting-out” began to be planned about the time that Lt-Gen. Tikka Khan took over the governorship of East Bengal, from the gentle, self-effacing Admiral Ahsan, and the military command there, from the scholarly Lt-Gen. Sahibzada Khan. That was at the beginning of March, when Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s civil disobedience movement was gathering momentum after the postponement of the assembly meeting from which the Bengalis hoped for so much. President Yahya Khan, it is said, acquiesced in the tide of resentment caused in the top echelons of the military establishment by the increasing humiliation of the West Pakistani troops stationed in East Bengal. The Punjabi Eastern Command at Dacca continues to dominate the policies of the Central Government. [It is perhaps worth pointing out that the Khans are not related: Khan is a common surname in Pakistan.]

When the army units fanned out in Dacca on the evening of March 25, in pre-emptive strikes against the mutiny planned for the small hours of the next morning, many of them carried lists of people to be liquidated. These included the Hindus and large numbers of Muslims; students, Awami Leaguers, professors, journalists and those who had been prominent in Sheikh Mujib’s movement. The charge, now publicly made, that the army was subjected to mortar attack from the Jaganath Hall, where the Hindu university students lived, hardly justifies the obliteration of two Hindu colonies, built around the temples on Ramna race course, and a third in Shakrepati, in the heart of the old city. Nor does it explain why the sizeable Hindu populations of Dacca and the neighbouring industrial town of Narayanganj should have vanished so completely during the round-the-clock curfew on March 26 and 27. There is similarly no trace of scores of Muslims who were rounded up during the curfew hours. These people were eliminated in a planned operation: an improvised response to Hindu aggression would have had different results.

A pencil flick, a man ‘disposed’

Touring Dacca on April 15 I found the heads of four students lying rotting on the roof of the Iqbal Hall hostel. The caretaker said they had been killed on the night of March 25. I also found heavy traces of blood on the two staircases and in four of the rooms. Behind Iqbal Hall a large residential building seemed to have been singled out for special attention by the army. The walls were pitted with bullet holes and a foul smell still lingered on the staircase, although it had been heavily powdered with DDT. Neighbours said the bodies of 23 women and children had been carted away only hours before. They had been decomposing on the roof since March 25. It was only after much questioning that I was able to ascertain that the victims belonged to the nearby Hindu shanties. They had sought shelter in the building as the army closed in.

THIS IS GENOCIDE conducted with amazing casualness. Sitting in the office of Major Agha, Martial Law Administrator of Comilla city, on the morning of’ April 19, I saw the off-hand manner in which sentences were meted out. A Bihari sub-inspector of police had walked in with a list of prisoners being held in the police lock-up. Agha looked it over. Then, with a flick of his pencil, he casually ticked off four names on the list.

“Bring these four to me this evening for disposal,” he said. He looked at the list again. The pencil flicked once more. “… and bring this thief along with, them.”

The death sentence had been pronounced over a glass of coconut milk. I was informed that two of the prisoners were Hindus, the third a “student,” and the fourth an Awami League organiser. The “thief,” it transpired, was a lad named Sebastian who had been caught moving the household effects of a Hindu friend to his own house.

Later that evening I saw these men, their hands and legs tied loosely with, a single rope, being led down the road to the Circuit House compound. A little after curfew, which was at 6 o’clock, a flock of squawking mynah birds were disturbed in their play by the thwacking sound of wooden clubs meeting bone and flesh.

CAPTAIN AZMAT of the Baluch Regiment had two claims to fame according to the mess banter. One was his job as ADC to Major-Gen Shaukat Raza, commanding officer of the 9th Division. The other was thrust on him by his colleagues’ ragging.

Azmat, it transpired, was the only officer in the group who had not made a “kill.” Major Bashir needled him mercilessly.

“Come on Azmat” Bashir told him one night, “we are going to make a man of you. Tomorrow we will see how you can make them run. It’s so easy.”

To underscore the point Bashir went into one of his long spiels. Apart from his duties as SSO, Bashir was also “education officer” ‘at Headquarters. He was the only Punjabi officer I found who could speak Bengali fluently. By general agreement Bashir was also a self-taught bore who gloried in the sound of his own voice.

A dari walla (bearded man) we were told, had come to see Bashir that morning to inquire about his brother, a prominent Awami League organiser of Comilla who had been netted by the army some days earlier. Dhor gaya, Bashir said he told him: “He has run away.” The old man couldn’t comprehend how his brother could have escaped on a broken leg. Neither could I. So Major Bashir, with a broad wink, enlightened me.

The record would show Dhor gaya: “shot while escaping.”

I NEVER DID find out whether Captain Azmat got his kill. The rebel Bengali forces who had dug in at Feni, seventy miles north of Chittagong on the highway to Comilla, had tied down the 9th Division by destroying all the bridges and culverts in the area. General Raza was getting hell from the Eastern Command at Dacca which was anxious to have the south-eastern border sealed against escaping rebels. It was also desperately urgent to open this only land route to the north to much-needed supplies that had been piling up in the port at Chittagong.

So General Raza was understandably waspish. He flew over the area almost daily. He also spent hours haranguing the brigade that, was bogged down at Feni. Captain Azmat, as usual, was the General’s shadow. I did not see him again. But if experience is any pointer, Azmat probably had to sweat out his “kill” — and the ragging — for another three weeks. It was only on May 8 that the 9th Division was able to clear Feni and the surrounding area. By then the Bengali rebels, forced out by relentless bombing and artillery barrages, had escaped with their weapons across the neighbouring border into India.

The escape of such large numbers of armed, hard-core regulars among the Bengali rebels was a matter of grave concern to Lt.-Col. Aslam Baig, G-1 at 9th Division headquarters. “The Indians,” he explained, will “obviously not allow them to settle there. It would be too dangerous. So they will be allowed in on sufferance as long as they keep making sorties across the border. Unless we can kill them off, we are going, to have serious trouble for a long time.”

Lt.-Col. Baig was a popular artillery officer who had done a stint in China after the India-Pakistan war when units of the Pakistan Army were converting to Chinese equipment. He was said to be a proud family man. He also loved flowers. He told me with unconcealed pride that during a previous posting at Comilla he had brought from China the giant scarlet waterlilies that adorn the pond opposite the headquarters. Major Bashir adored him. Extolling one officer’s decisiveness Bashir told me that once they had caught a rebel officer there was a big fuss about what should be done with him. “While the others were telephoning all over for instructions,” he said, “he solved the problem. Dhor gaya. Only the man’s foot was left sticking out of the ditch.”

IT IS HARD to imagine so much brutality in the midst of so much beauty. Comilla was blooming when I went there towards the end of April. The rich green carpet of rice paddies spreading to the horizon on both sides of the road was broken here and there by bright splashes of red. That was the Gol Mohor, aptly dubbed the “Flame of the Forest,” coming to full bloom. Mango and coconut trees in the villages dotting the countryside were heavy with fruit. Even the terrier-sized goats skipping across the road gave evidence of the abundance of nature in Bengal. “The only, way you can tell the male from the female,” they told me,” is that all the she-goats are pregnant.”

Fire and murder their vengeance

In one of the most crowded areas of the entire world — Comilla district has a population density of 1,900 to the square mile — only man was nowhere to be seen.

“Where are the Bengalis?” I had asked my escorts in the strangely empty streets of Dacca a few days earlier. “They have gone to the villages”, was the stock reply. Now, in the countryside, there were still no Bengalis. Comilla town like Dacca was heavily shuttered. And in ten miles on the road to Laksham, past silent villages, the peasants I saw could have been counted on the fingers of both hands.

There were, of course, soldiers — hundreds of unsmiling men in khaki, each with an automatic rifle. According to orders, the rifles never left their hands. The roads are constantly patrolled by tough, trigger-happy men. Wherever the army is, you won’t find Bengalis.

Martial law orders, constantly repeated on the radio and in the Press, proclaim the death penalty for any one caught in the act of sabotage. If a road is obstructed or a bridge damaged or destroyed, all houses within 10 yards of the spot are liable to be demolished and their inhabitants rounded up.

The practice is even more terrible than anything the words could suggest. “Punitive action” is something that the Bengalis have come to dread.

We saw what this meant when we were approaching Hajiganj, which straddles the road to Chandpur, on the morning of April 17. A few miles before Hajiganj, a 15-foot bridge had been damaged the previous night by rebels who were still active in the area. According to Major Rathore (G-2 Ops.), an army unit had immediately been sent out to take punitive action. Long spirals of smoke could be seen on all sides up to a distance of a quarter of a mile from the damaged bridge. And as we carefully drove over a bed of wooden boards, with which it had been hastily repaired, we could see houses in the village on the right beginning to catch fire.

At the back of the village some jawans were spreading the flames with dried coconut fronds. They make excellent kindling and are normally used for cooking. We could also see a body sprawled between the coconut trees at the entrance to the village. On other side of the road another village in the rice paddies showed evidence of the fire that had gutted more than a dozen bamboo and mat huts. Hundreds of villagers had escaped before the army came. Others, like the man among the coconut trees, were slow to get away.

As we drove on, Major Rathore said, “They brought it on themselves.” I said it was surely too terrible a vengeance on innocent people for the acts of a handful of rebels. He did not answer.

A few hours later when we were again passing through Hajiganj on the way back from Chandpur, I had my first exposure to the savagery of a “kill and burn mission”.

We were still caught up in the aftermath of a tropical storm which had hit the area that afternoon. A heavy overcast made ghostly shadows on the mosque towering above the town. Light drizzle was beginning to wet the uniforms of Captain Azhar and the four jawans riding in the exposed escort jeep behind us.

We turned a corner and found a convoy of trucks parked outside the mosque. I counted seven, all filled with jawans in battle dress. At the head of the column was a jeep. Across the road two men, supervised by a third, were trying to batter down the door of one of more than a hundred shuttered shops lining the road. The studded teak wood door was beginning to give under the combined assault of two axes as Major Rathore brought the Toyota to a halt.

“What the hell are you doing ?”

The tallest of the trio, who was supervising the break-in, turned and peered at us. “Mota,” (Fatty) he shouted, “what the hell do you think we are doing?”

Recognising the voice, Rathore drew a water-melon smile. It was, he informed me, his old friend “Ifty” —Major Iftikhar of the 12th Frontier Force Rifles.

Rathore: “I thought someone was looting.”

Iftikhar: “Looting? No. We are on kill and burn.”

Waving his hand to take in the shops, he said he was going to destroy the lot.

Rathore: “How many did you get?”

Iftikhar smiled bashfully.

Rathore: “Come on. How many did you get?”

Iftikhar: “Only twelve. And by God we were lucky to get them. We would have lost those, too, if I hadn’t sent my men from the back.”

Prodded by Major Rathore, Iftikhar then went on to describe vividly how after much searching in Hajiganj he had discovered twelve Hindus hiding in a house on the outskirts of the town. These had been “disposed of.” Now Major Iftikhar was on the second part of his mission: burn.

By this time the shop’s door had been demobilised and we found ourselves looking into one of those tiny catch-all establishments which, in these parts, go under the title “Medical & Stores.” Under the Bengali lettering the signboard carried in English the legend “Ashok Medical & Stores.” Lower down was painted “Prop. A. M. Bose.” Mr. Bose, like the rest of the people of Hajiganj, had locked and run.

In front of the shop a small display cabinet was crammed with patent medicines, cough syrups, some bottles of mango squash, imitation jewellery, reels of coloured cotton, thread and packets of knicker elastic. Iftikhar kicked it over, smashing the light wood-work into kindling. Next he reached out for some jute shopping bags on one shelf. He took some plastic toys from another. A bundle of handkerchiefs and a small bolt of red cloth joined the pile on the floor. Iftikhar heaped them all together and borrowed a matchbox from one of the jawans sitting in our Toyota. The jawan had ideas of his own. Jumping from the vehicle he ran to the shop and tried to pull down one of the umbrellas hanging from the low ceiling of the shop. Iftikhar ordered him out.

Looting, he was sharply reminded, was against orders.

Iftikhar soon had a fire going. He threw burning jute bags into one corner of the shop, the bolt of cloth into another. The shop began to blaze. Within minutes we could hear the crackle of flames behind shuttered doors as the fire spread to the shop on the left, then on to the next one.

At this point Rathore was beginning to get anxious about the gathering darkness. So we drove on.

When I chanced to meet Major Iftikhar the next day he ruefully told me: “I burnt only sixty houses. If it hadn’t rained I would have got the whole bloody lot.”

Approaching a village a few miles from Mudarfarganj we were forced to a halt by what appeared to be a man crouching against a mud wall. One of the jawans warned it might be a fauji sniper. But after careful scouting it turned out to be a lovely young Hindu girl. She sat there with the placidity of her people, waiting for God knows who. One of the jawans had been ten years with the East Pakistan Rifles and could speak bazaar Bengali. He was told to order her into the village. She mumbled something in reply, but stayed where she was, but was ordered a second time. She was still sitting there as we drove away. “She has,” I was informed, “nowhere to go — no family, no home.”

Major Iftikhar was one of several officers assigned to kill and burn missions. They moved in after the rebels had been cleared by the army with the freedom to comb-out and destroy Hindus and “miscreants” (the official jargon for rebels) and to burn down everything in the areas from which the army had been fired at.

This lanky Punjabi officer liked to talk about his job. Riding with Iftikhar to the Circuit House in Comilla on another occasion he told me about his latest exploit.

“We got an old one,” he said. “The bastard had grown a beard and was posing as a devout Muslim even called himself Abdul Manan. But we gave him a medical inspection and the game was up.”

Iftikhar continued: “I wanted to finish him there and then, but my men told me such a bastard deserved three shots. So I gave him one in the balls, then one in the stomach. Then I finished him off with a shot in the head.”

When I left Major Iftikhar he was headed north to Bramanbaria. His mission: Another kill and burn.

OVERWHELMED WITH TERROR the Bengalis have one of two reactions. Those who can run away just seem to vanish. Whole towns have been abandoned as the army approached. Those who can’t run away adopt a cringing servility which only adds humiliation to their plight.

Chandpur was an example of the first.

In the past this key river port on the Meghna was noted for its thriving business houses and gay life. At night thousands of small country boats anchored on the river’s edge made it a fairy land of lights. On April 18 Chandpur was deserted. No people, no boats. Barely one per cent of the population had remained. The rest, particularly the Hindus who constituted nearly half the population, had fled.

Weirdly they had left behind thousands of Pakistani flags fluttering from every house, shop and rooftop. The effect was like a national day celebration without the crowds. It only served to emphasise the haunted look.

The flags were by way of insurance.

Somehow the word had got around that the army considered any structure without a Pakistani flag to be hostile and consequently to be destroyed. It did not matter how the Pakistani flags were made, so long as they were adorned with the crescent and star. So they came in all sizes, shapes and colours. Some flaunted blue fields, instead of the regulation green. Obviously they had been hastily put together with the same material that had been used for the Bangladesh flag. Indeed, blue Pakistani flags were more common than the green. The scene in Chandpur was repeated in Hajiganj, Madarfarganj, Kasba, Brahmanbaria; all ghost towns gay with flags.

A ‘parade’ and a knowing wink

Laksham was an example of the other reaction: cringing.

When I drove into the town the morning after it had been cleared of the rebels, all I could see was the army and literally thousands of Pakistani flags. The major in charge there had camped in the police station, and it was there that Major Rathore took us. My colleague, a Pakistani TV cameraman, had to make a propaganda film about the “return to normalcy” in Laksham — one of the endless series broadcast daily showing welcome parades and “peace meetings.”

I wondered how he could manage it but the Major said it would be no sweat. “There are enough of these bastards left to put on a good show. Give me 20 minutes.”

Lieutenant Javed of the 39 Baluch was assigned the task of rounding up a crowd. He called out to an elderly bearded man who had apparently been brought in for questioning. The man, who later gave his name as Moulana Said Mohammad Saidul Huq, insisted he was a “staunch Muslim Leaguer and not from the Awami League” (The Muslim League led the movement for an independent Pakistan in 1947). He was all too eager to please. “I will very definitely get you at least 60 men in 20 minutes,” he told Javed. “But if you give me two hours I will bring 200.”

Moulana Saidul Huq was as good as his word. We had hardly drunk our fill of the deliciously refreshing coconut milk that had been thoughtfully supplied by the Major when we heard shouts in the distance. “Pakistan Zindabad!” “Pakistan army Zindabad!” “Muslim League Zindabad!” they were chanting. (Zindabad is Urdu for “Long live!”) Moments later they marched into view, a motley crowd of about 50 old and decrepit men and knee-high children, all waving Pakistani flags and shouting at the top of their voices. Lt. Javed gave me a knowing wink.

Within minutes the parade had grown into a “public meeting” complete with a make-shift public address system and a rapidly multiplying group of would-be speakers.

Mr. Mahbub-ur-Rahman was pushed forward to make the address of welcome to the army. He introduced himself as “N.F. College Professor of English and Arabic who had also tried for History and is a life-time member of the great Muslim League Party.”

Introduction over, Mahbub-ur-Rahman gave forth with gusto. “Punjabis and Bengalis,” he said, “had united for Pakistan and we had our own traditions and culture. But we were terrorised by the Hindus and the Awami Leaguers and led astray. Now we thank God that the Punjabi soldiers have saved us. They are the best soldiers in the world and heroes of humanity. We love and respect them from the bottom of our hearts.” And so on, interminably, in the same vein.

After the “meeting” I asked the Major what he thought about the speech, “Serves the purposes,” he said, “but I don’t trust that bastard. I’ll put him on my list.”

THE AGONY of East Bengal is not over. Perhaps the worst is yet to come. The army is determined to go on until the “clean-up” is completed. So far the job is only half done. Two divisions of the Pakistan army, the 9th and the 16th, were flown out from West Pakistan to “sort out” the Bengali rebels and the Hindus. This was a considerable logistical feat for a country of Pakistan’s resources. More than 25,000 men were moved from the west to the east. On March 28 the two divisions were given 48 hours’ notice to move. They were brought by train to Karachi from Kharian and Multan. Carrying only light bed rolls and battle packs (their equipment was to follow by sea), the troops were flown out to Dacca by PIA, the national airline. Its fleet of seven Boeings was taken off international and domestic routes and flew the long haul (via Ceylon) continuously for 14 days. A few Air Force transport aircraft helped.

The troops went into action immediately with equipment borrowed from the 14th Division which till then constituted the Eastern Command. The 9th Division, operating from Comilla, was ordered to seal the border in the east against movement of rebels and their supplies. The 16th Division, with headquarters at Jessore, had a similar task in the western sector of the province. They completed these assignments by the third week of May. With the rebels — those who have not been able to escape to India — boxed in a ring of steel and fire, the two army divisions are beginning to converge in a relentless comb-out operation. This will undoubtedly mean that the terror experienced in the border areas will now spread to the middle point. It could also be more painful. The human targets will have nowhere to run to.

On April 20 Lt.-Col. Baig, the flower-loving G-1 of the 9th Division, thought that the comb-out would take two months, to the middle of June. But this planning seems to have misfired. The rebel forces, using guerilla tactics, have not been subdued as easily as the army expected. Isolated and apparently uncoordinated, the rebels have nonetheless bogged down the Pakistan army in many places by the systematic destruction of roads and railways, without which the army cannot move. The 9th Division for one was hopelessly behind schedule. Now the monsoon threatens to shut down the military operation with three months of cloudbursts.

For the rainy season, the Pakistan government obtained from China in the second week of May, nine shallow draught river gunboats. More are to come. These 80-ton gunboats with massive firepower will take over some of the responsibilities hitherto allotted to the air force and artillery, which will not be as effective when it rains. They will be supported by several hundred country craft which have been requisitioned and converted for military use by the addition of outboard motors. The army intends to take to the water in pursuit of the rebels.

Colonisation of East Bengal

There is also the clear prospect of famine, because of the breakdown of the distribution system. Seventeen of the 23 districts of East Pakistan are normally short of food and have to be supplied by massive imports of rice and wheat. This will not be possible this year because of the civil war. Six major bridges and thousands of smaller ones have been destroyed, making the roads impassable in many places. The railway system has been similarly disrupted though the government claims it is “almost normal.”

The road and rail tracks between the port of Chittagong and the north have been completely disrupted by the rebels who held Feni, a key road and rail junction, until May 7. Food stocks cannot move because of this devastation. In normal times only 15% of food movements from Chittagong to upcountry areas were made by boat. The remaining 85% was moved by road and rail. Even a 100% increase in the effectiveness of river movement will leave 70% of the food stocks in the warehouses of Chittagong.

Two other factors must be added. One is large-scale hoarding of grain by people who have begun to anticipate the famine. This makes a tight position infinitely more difficult. The other is the government of Pakistan’s refusal to acknowledge the danger of famine publicity. Lt. Gen. Tikka Khan, the Military Governor of East Bengal, acknowledged in a radio broadcast on April 18 that he was gravely concerned about food supplies. Since then the entire government machinery has been used to suppress the fact of the food shortage. The reason is that a famine, like the cyclone before it, could result in a massive outpouring of foreign aid — and with it the prospect of external inspection of distribution methods. That would make it impossible to conceal from the world the scale of the pogrom. So the hungry will be left to die until the clean-up is complete.

Discussing the problem in his plush air-conditioned office in Karachi recently the chairman of the Agricultural Development Bank, Mr. Qarni, said bluntly: “The famine is the result of their acts of sabotage. So let them die. Perhaps then the Bengalis will come to their senses.”

THE MILITARY GOVERNMENT’S East Bengal policy is so apparently contradictory and self-defeating that it would seem to justify the assumption that the people who rule Pakistan cannot make up their minds. Having committed the initial error of resorting to force, the government, on this view, is stubbornly and stupidly muddling through.

There is, superficially, logic in this reasoning.

On the one hand, it is true that there is no let up in the reign of terror. The policy of subjugation is certainly being pursued with vigour in East Bengal. This is making thousands of new enemies for the government every day and making only more definitive the separation of the two wings of Pakistan.

On the other hand, no government could be unaware that this policy must fail (there are just not enough West Pakistanis to hold down the much greater numbers in East Bengal indefinitely.) For hard administrative and economic reasons, and because of the crucial consideration of external development assistance, especially from America, it will be necessary to achieve a political settlement as quickly as possible. President Yahya Khan’s press conference on May 25 suggests that he acknowledges the force of these factors: And he said he would announce his plan for representative government in the middle of June.

All this would seem to indicate that Pakistan’s military government is moving paradoxically, in opposite directions, to compound the gravest crisis in the country’s 24-years history.

This is widely held view. It sounds logical, But is it true?

My own view is that it is not. It has been my unhappy privilege to have had the opportunity to observe at first hand both what Pakistan’s leaders say in the West, and what they are doing in the East.

I think that in reality there is no contradiction in the government’s East Bengal policy. East Bengal is being colonised.

This is not an arbitrary opinion of mine. The facts speak for themselves.

The first consideration of the army has been and still is the obliteration of every trace of separatism in East Bengal. This proposition is upheld by the continuing slaughter and by everything else that the government has done in both East and West Pakistan since March 25. The decision was coldly taken by the military leaders, and they are going through with it — all too coldly.

No meaningful or viable political solution is possible in East Bengal while the pogrom continues.

The crucial question is: Will the killing stop?

I was given the army’s answer by Major-General Shaukat Raza, Commanding Officer of the 9th Division, during our first meeting at Comilla on April 16.

“You must be absolutely sure,” he said, “that we have not undertaken such a drastic and expensive operation — expensive both in men and money — for nothing. We’ve undertaken a job. We are going to finish it, not hand it over half done to the politicians so that they can mess it up again. The army can’t keep coming back like this every three or four years. It has a more important task. I assure you that when we have got through with what we are doing there will never be need again for such an operations.”

Major-General Shaukat Raza is one of the three divisional commanders in the field. He is in a key position. He is not given to talking through his hat.

Significantly, General Shaukat Raza’s ideas were echoed by every military officer I talked to during my 10 days in East Bengal. And President Yahya Khan knows that the men who lead the troops on the ground are the de facto arbiters of Pakistan’s destiny.

The single-mindedness of the army is underscored by the military operation itself. By any standard, it is a major venture. It is not something that can be switched on and off without the most grave consequences.

Army committed to remain

The army has already taken a terrible toll in dead and injured. It was privately said in Dacca that more officers have been killed than men and that the casualty list in East Bengal already exceeds the losses in the India-Pakistan war of September, 1965. The army will certainly not write off these “sacrifices” for illusory political considerations that have proved to be so worthless in the past.

Militarily — and it is soldiers who will be taking the decision — to call a halt to the operation at this stage would be indefensible. It would only mean more trouble with the Bengali rebels. Implacable hatred has been displayed on both sides. There can be no truce or negotiated settlement; only total victory or total defeat. Time is on the side of the Pakistan army, not of the isolated, uncoordinated and ill-equipped rebel groups. Other circumstances, such as an expanded conflict which takes in other powers, could of course alter the picture. But as it stands today the Pakistan army has no reason to doubt that it will eventually achieve its objective. That is why the casualties are stolidly accepted.

The enormous financial outlay already made on the East Bengal operation and the continuing heavy cost also testify to the government’s determination. The reckless manner in which funds have been poured out makes clear that the military hierarchy, having taken a calculated decision to use force, has accepted the financial outlay as a necessary investment. It was not for nothing that 25,000 soldiers were airlifted to East Bengal, a daring and expensive exercise. These two divisions, the 9th and the 16th, constituted the military reserve in West Pakistan. They have now been replaced there by expensive new recruitment.

The Chinese have helped with equipment, which is pouring down the Karakorum highway. There is some evidence that the flood is slowing down: perhaps the Chinese are having second thoughts about their commitments to the military rulers of Pakistan. But the Pakistan government has not hesitated to pay cash from the bottom of the foreign exchange barrel for more than $ 1million worth of ammunition to European arms suppliers.

Conversations with senior military officers in Dacca, Rawalpindi and Karachi confirm that they see the solution to this problem in the speedy completion of the East Bengal operation, not in terms of a pull-out. The money required for that purpose now takes precedence over all other governmental expenditure. Development has virtually come to a halt.

In one sentence, the government is too far committed militarily to abandon the East Bengal operation, which it would have to do if it sincerely wanted a political solution. President Yahya Khan is riding on the back of a tiger. But he took a calculated decision to climb up there.

SO THE ARMY is not going to pull out. The government’s policy for East Bengal was spelled out to me in the Eastern Command headquarters at Dacca. It has three elements:¬

(I) The Bengalis have proved themselves “unreliable” and must be ruled by West Pakistanis;

(2) The Bengalis will have to be re-educated along proper Islamic lines. The “Islamisation of the masses” — this is the official jargon — is intended to eliminate secessionist tendencies and provide a strong religious bond with West Pakistan;

(3) When the Hindus have been eliminated by death and flight, their property will be used as a golden carrot to win over the under-privileged Muslim middle¬class. This will provide the base for erecting administrative and political structure in the future.

This policy is being pursued with the utmost blatancy.

Because of the mutiny, it has been officially decreed that there will not, for the present, be any further recruitment of Bengalis in the defence forces. Senior air force and navy officers, who were not in anyway involved, have been moved “as a precaution” to non-sensitive positions. Bengali fighter pilots, among them some of the aces of the air force, had the humiliation of being grounded and moved to non-flying duties. Even PIA air crews operating between the two wings of the country have been strained clean of Bengalis.

The East Pakistan Rifles, once almost exclusively a Bengali para-military force, has ceased to exist since the mutiny. A new force, the Civil Defence Force, has been raised by recruiting Biharis and volunteers from West Pakistan. Biharis, instead of Bengalis, are also being used as the basic material for the police. They are supervised by officers sent out from West Pakistan and by secondment from the army. The new superintendent of police at Chandpur at the end of April was a military police major.

Hundreds of West Pakistani government civil servants, doctors, and technicians for the radio, TV, telegraph and telephone services have already been sent out to East Pakistan; More are being encouraged to go with the promise of one and two-step promotions. But the transfer, when made, is obligatory. President Yahya recently issued an order making it possible to transfer civil servants to any part of Pakistan against their will.

The universities ‘sorted out’

I was told that all the commissioners of East Bengal and the district deputy commissioners will in future be either Biharis or civil officers from West Pakistan. The deputy commissioners of the districts were said to be too closely involved with the Awami League secessionist movement. In some cases, such as that of the deputy commissioner of Comilla, they were caught and shot. That particular officer had incurred the wrath of the army on March 20 when he refused to requisition petrol and food supplies “without a letter from Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.”

The government has also come down hard on the universities and colleges of East Bengal. They were considered the hot beds of conspiracy and they are being “sorted out”. Many professors have fled. Some have been shot. They will be replaced by fresh recruitment from West Pakistan.

Bengali officers are also being weeded out of sensitive positions in the Civil and Foreign Services. All are currently being subjected to the most exhaustive screening.

This colonisation process quite obviously does not work even half as efficiently as the administration wishes. I was given vivid evidence of this by Major Agha, Martial Law Administrator of Comilla. He had been having a problem getting the local Bengali executive engineers to go out and repair the bridges and roads that had been destroyed or damaged by the rebels. This task kept getting snarled in red tape, and the bridges remained unrepaired. Agha, of course, knew the reason. “You can’t expect them to work,” he told me, “when you have been killing them and destroying their country. That at least is their point of view, and we are paying for it.”

CAPTAIN DURRANI of the Baluch Regiment, who was in charge of the company guarding the Comilla airport, had his own methods of dealing with the problem. “I have told them,” he said with reference to the Bengalis maintaining the control tower, “that I will shoot anyone who even looks like he is doing something suspicious.” Durranni had made good his word. A Bengali who had approached the airport a few nights earlier was shot. “Could have been a rebel,” I was told. Durrani had another claim to fame. He had personally accounted more than 60 men while clearing the villages surrounding the airport.

The harsh reality of colonisation in the East is being concealed by shameless window dressing. For several weeks, President Yahya Khan and Lt.-Gen. Tikka Khan have been trying to get political support in East Pakistan for what they are doing. The results have not exactly been satisfying. The support forthcoming so far has been from people like Moulvi Farid Ahmad, a Bengali lawyer in Dacca, Fazlul Quader Chaudhury and Professor Ghulam Azam, of the Jamaat-e-Islami, all of whom were soundly beaten in the general elections last December.

The only prominent personality to emerge for this purpose has been Mr. Nurul Amin, an old Muslim Leaguer and former chief minister of the province, who was one of only two non-Awami Leaguers to be elected to the National Assembly. He is now in his seventies. But even Nurul Amin has been careful not to be too effusive. His two public statements to date have been concerned only with the “Indian interference.”

Bengalis look with scorn on the few who “collaborate.” Farid Ahmad and Fazlul Quader Chaudhury are painfully aware of this. Farid Ahmad makes a point of keeping his windows shuttered and only those who have been scrutinised and recognised through a peephole in the front door are allowed into the house.

By singularly blunt methods the government has been able to get a grudging acquiescence from 31 Awami Leaguers who had been elected to the national and provincial assemblies. They are being kept on ice in Dacca, secluded from all but their immediate families, for the big occasion when “representative government” is to be installed. But clearly they now represent no one but themselves.

ABDUL BARI, the tailor who was lucky to survive, is 24 years old. That is the same age as Pakistan. The army can of course hold the country together by force. But the meaning of what it has done in East Bengal is that the dream of the men who hoped in 1947 that they were founding a Muslim nation in two equal parts has now faded. There is now little chance for a long time to come that Punjabis in the West and Bengalis in the East will fell themselves equal fellow-citizens of one nation. For the Bengalis, the future is now bleak: the unhappy submission of a colony to its conquerors.