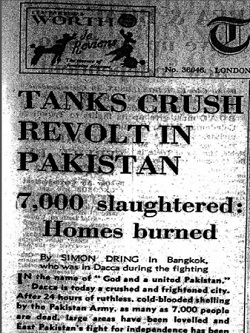

Tanks Crush Revolt in Pakistan

7,000 Slaughtered: Homes Burned

One of the biggest massacres of the entire operation in Dacca took place in the Hindu area of the old town. There the soldiers made the people come out of their houses and then just shot them in groups. This area, too, was eventually razed.

A group of Hindu Pakistanis living around a temple in the middle of racecourse were all killed, apparently for no reason at all except they were out in the open.

Simon Dring

Published in Daily Telegraph (London) on 30 March 1971

BY SIMON DRING in Bangkok, who was in Dacca during the fighting

In the name of “God and united Pakistan,” Dacca is today a crushed and frightened city.

After 24 hours of ruthless, cold-blooded shelling by the Pakistan Army as many as 7,000 people are dead, large areas have been levelled and East Pakistan’s fight for independence has been brutally put to an end.

Despite claims by President Yahya Khan, head of the country’s military government, that the situation is now calm tens of thousands of people are fleeing to the countryside, the city streets are almost deserted and the killings are still going on in other parts of the province.

But there is no doubt that troops supported by tanks control the towns and major population centres and that resistance is minimal and so far ineffective.

Even so people are still being shot at the slightest provocation, and buildings are still being indiscriminately destroyed.

And the military appears to be more determined each day to assert its control over the 73 million Bengalees in the East wing.

It is impossible accurately to assess what all this has so far cost in terms of innocent human lives. But reports beginning to filter in from the outlying areas, Chittagong, Comilla and Jessore, put the figure, including Dacca, in the region of 15,000 dead.

Only the horror of the military action can be properly gauged — the students dead in their beds, the butchers in the markets killed behind their stalls, the women and children roasted alive in their houses, the Pakistanis of Hindu religion taken out and shot ‘en masse’, the bazaars and shopping areas razed by fire and the Pakistani flag that now flies over every building in the capital.

Military casualties are not known but at least two soldiers have been wounded and one officer killed.

The Bengali uprising seems to be well and truly over for the moment. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was seen taken away by the Army and nearly all the top members of his Awami League party have also been arrested.

Armoured Attack

Leading political activists have been taken in, others have been murdered and the offices of two newspapers which supported the Sheikh’s movement have been destroyed.

But the first target as the tanks rolled into Dacca on the night of the 25th was the students.

An estimated three battalions of troops were used in the attack on Dacca — one armoured, one artillery and one infantry. They started leaving the barracks shortly before 10 p.m.

By 11 p.m. firing had broken out and the people who had started hastily erecting makeshift barricades — overturned cars, trees, stumps, furniture, concrete piping — became early casualties as the troops rolled into town.

Sheikh Mujib was telephoned and warned that something was happening, but he refused to leave his house. “If I go into hiding they will burn the whole of Dacca to find me,” he told an aide who escaped arrest.

200 Students Killed

The students were also warned but those who were still around later said that most thought they would only be arrested.

Led by American supplied M24 World War II tanks, one column of troops sped to Dacca University shortly after midnight. Troops took over the British Council library and used it as a fire-base to shell nearby dormitory areas.

Caught completely by surprise, some 200 students were killed in Iqbal Hall, headquarters of the militantly antigovernment students’ union, as shells slammed into the building and the their rooms were sprayed with machine-gun fire.

Two days later bodies were still smouldering in their burnt out rooms, others were scattered outside and more floated in a nearby lake. An art student lay sprawled across his easel.

Seven teachers died in their quarters and a family of 12 were gunned down as they hid in an out-house.

The military removed many of the bodies, but the 30 still there could never have accounted for all the blood in the corridors of Iqbal Hall.

At another hall the dead were buried by the soldiers in a hastily-dug mass grave and then bulldozed over by tanks.

People living near the university were caught in the fire too and 200 yards of shanty houses running alongside a railway line were destroyed.

Army patrols also razed a nearby market area, running down between the stalls, killing their owners as they slept. Two days later, when it was possible to get out and see all this, some of the men were still lying as though asleep, their blankets pulled up over their shoulders.

In the same district the Dacca Medical College received direct bazooka fire and a mosque was badly damaged.

Police H.Q. Attacked

As the university came under attack columns of troops moved in on the Rajarbag headquarters of the East Pakistan police on the other side of the city.

Tanks opened fire first and then the troops moved in and leveled the men’s sleeping quarters, firing incendiary rounds into the buildings.

It was not known, even by people living opposite how many died, but out of the 1100 police based there, not many are believed to have escaped.

As this was going on other units had surrounded the Sheikh’s house. When contacted shortly before 1 a.m. he was expecting an attack any minute and that he had sent everyone except his servants and a bodyguard away to safety.

A neighbour said that 1.10 a.m. one tank, an armoured car and trucks loaded with troops drove down the street firing over the house.

“Sheikh, you should come down,” an officer called out in English as they stopped outside.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman replied by stepping out on to his balcony and saying, “Yes, I am ready but there is no need to fire; all you need to have done was call me on the telephone and I would have come.”

The officer then walked into the garden of the house and told the Sheikh: “You are arrested.”

He was taken away, along with three servants, an aide and his bodyguard who was badly beaten up when he started to insult the officer.

Documents Taken

As he was driven of — presumably to Army headquarters the soldiers moved into house, took away all the documents, smashed everything in sight, locked the garden gate, shot down green, red and yellow “Bangladesh” (Free Bengal) flag and drove away.

By 2 a.m. on the 26th fires were burning all over the city. Troops had occupied the university and surrounding areas and were busy killing off students still in hiding and replacing independence flags with Pakistani national standards.

There was still heavy shelling in some areas but the fighting was noticeably beginning to slacken. Opposite the Intercontinental Hotel, a platoon of troops, stormed the empty offices of Dacca’s ‘People’ newspaper, burning it down along with most houses in the area and killing a lone night-watchman.

Shortly before dawn most firing had stopped and as the sun came up an eerie silence settled over the city, deserted and completely dead except for the noise of the crows and the occasional convoy of troops.

But the worst was yet to come. At midday, again without any warning, columns of troops poured into the old section of the city where more than a million people live in a sprawling maze of narrow, winding streets.

For the next 11 hours they proceeded systematically to devastate large areas of the old town where Sheikh Mujib had some of his strongest support among the people in Dacca.

English Road, French Road, Niar Bazaar, City Bazaar meaningless names but home to thousand of people were burnt to the ground.

“They suddenly appeared at the end of the street,” said one old man living in the French Road-Niar Bazaar area. “Then they drove down it firing into all the houses.”

The leading unit was followed by soldiers carrying cans of petrol. Those who tried to escape were shot. Those who stayed were burnt alive. About 700 men, women and children died there that day between midday and two o’clock.

The same was repeated in at least three other areas, all of them covering anything up to half a square mile or more.

As they left the soldiers took those dead they could away with them in trucks and moved on to their next target. Police station in the old town were also attacked.

“I am looking for my constables,” a Police Inspector said on Saturday morning as he wandered through the ruins of one of the bazaars. “I have 240 in my district and so far I have found only 30 of them — all dead.”

One of the biggest massacres of the entire operation in Dacca took place in the Hindu area of the old town. There the soldiers made the people come out of their houses and then just shot them in groups. This area, too, was eventually razed.

The troops stayed on in the old city in force until about 11 p.m. on the 26th driving about with local Bengali informers.

The soldiers would fire a flare and the informer would point out the houses of staunch Awami League supporters. The house would then be destroyed — either with direct tank or recoilless rifle fire or with a can of petrol.

Firing continued in these areas until early on Sunday morning but the main bulk of the operation in the city was completed by the night of the 26th — almost exactly 24 hours after it began.

One of the last targets was the Bengali language daily newspaper ‘Ittefaq’. Over 400 people had taken shelter in its offices when the fighting started.

At 4 o’clock on the afternoon of 26th four tanks appeared in the road outside. By 4.30 p.m. the building was an inferno. By Saturday morning only the charred remains of the corpses were left.

As quickly as they appeared the troops disappeared off the streets. On Saturday morning the radio announced the curfew would be lifted from 7 a.m. until 4 p.m.

It then repeated the Martial Law Regulations banning all political activity, announcing Press censorship and ordering all Government employees to report back for work and all privately-owned weapons to be handed in.

Thousands Flee

Magically the city returned to life and panic set in. By 10 a.m., with palls of black smoke still hanging over large areas of the old town and out in the distance towards the industrial areas, the streets were packed with fleeing people.

By car, in rickshaw but mostly on foot carrying their possessions with them the people of Dacca were leaving. By midday they were on the move in their tens of thousands.

“Please give me a lift, I’m an old man,” “In the name of Allah help me.” “Take my children with you,” came the pleas.

Silent and unsmiling they passed and saw what the Army had done. It had been a thorough job, carefully planned and meticulously executed and they looked the other way and kept on walking.

Down near one of the markets a shot was heard. Within second 2,000 people were running, but it had only been someone going to join the queues already forming to hand in their weapons.

The Government offices remained almost empty. Most employees were leaving for their villages.

Those who are not fleeing wandered aimlessly around the smoking debris of what were once their homes, lifting the blackened, twisted sheets of corrugated iron used in most shanty areas as roofing materials to save what they could from the ashes.

Nearly every other car, if it was not taking people out into the countryside, was flying a Red Cross and convoying dead and wounded to the hospitals.

And in the middle of it all occasional convoys of troops would appear, the soldiers peering unsmiling down the muzzles of their guns at the silent crowds.

On the Friday night as they pulled back to their barracks they shouted “Narai Tukbir”, an old Arabic war cry meaning “We have won the war.”

On Saturday when they spoke it was to shout “Pakistan Zindabad”, “Long Live Pakistan”.

Most people took the hint. Before the curfew was reimposed the national flag of Pakistan, apart from petrol, was the hottest selling item in the market.

As if to protect their property in their absence, the last thing a family would do before they locked up their house would be to raise the flag.

At four o’clock the streets emptied again, the troops reappeared and silence fell once more over Dacca.

But firing broke out again almost immediately. “Anybody out of doors after four will be shot,” the radio had announced.

A small boy running across the street outside the Intercontinental two minutes after the curfew was stopped was stopped, slapped four times in the face by an officer and taken away in a jeep.

Another unfortunate night-watchman, this time at the Dacca Club, a leftover bar from the colonial days, was shot when he went to shut the gate of the club.

A group of Hindu Pakistanis living around a temple in the middle of racecourse were all killed, apparently for no reason at all except they were out in the open.

And refugees who came back into the city when they found roads leading out were blocked by the Army told how many had been killed as they tried to walk across country to avoid the troops.

Beyond those roadblocks is more or less a no man’s land, where the clearing operations are still going on. What is happening out there is anybody’s guess — except the Army’s.

Many people took to the river to try to escape the crowds on the roads. But they ran the risk of being left stranded waiting for a boat when curfew fell.

Where one such group was sitting on Saturday afternoon, there were only bloodstains next morning.

“Traitors” Charge

Hardly anywhere was the evidence of organised resistance to the troops in Dacca or anywhere else in the province. Even the West Pakistani officers scoffed at the idea of anybody putting up a fight.

“These men,” said one Punjabi lieutenant, “could not kill us if they tried.”

“Things are much better now,” said another officer. “Nobody can speak out or come out. If they do we will kill them. They have spoken enough. They are traitors and we are not. We are fighting in the name of God and a united Pakistan.”

The operation, apparently planned and led by Gen. Tikka Khan, the West Pakistani military governor of the East, has succeeded in driving every last drop of resistance out of the people of Bengal.

Only the propaganda machine of the Indian Government is keeping the fight going apart from a Leftist underground group operating a clandestine “Bangla Desh” radio somewhere outside Dacca.

Even if time erases the scars that marks the end of the dream that the people of East Pakistan thought was democratically theirs, it will take more than a generation before they live down the fear instilled in their minds by the tragic and horrifying massacres of last week.

If anything is to be salvaged from the ruins of Sheikh Mujib’s movement, it is the realisation that the Army is not to be under-estimated again and that for all the speech-making of President Yahya about the returning of power to the people, the regime did not really ever intend to abide by the results of any elections — fairly won or not.